The sky is falling, the end draws nigh: the Gustavo Dudamel era is over in LA.

Or at least it will be when he departs for New York in 2026. If over the past few weeks you’ve noticed distant moaning of a westerly origin, it’s likely the sound of the newly-assembled LA Phil search committee, going name by name down a whiteboard of possible successors, circling contenders, erasing pretenders. It’s a lengthy and unenviable process.

But what if we could bypass the process – or at least speed it up – and get a short list together faster?

Today we’ll do just that, using something rigged up in the Classical Dark Arts lab called the Data-driven Utility for Determining Artistic Merit and Evaluating Leadership, or D.U.D.A.M.E.L. It’s an algorithm for identifying and evaluating potential candidates for the LA Phil search committee. DUDAMEL crunches spreadsheets of data extracted from across the web and narrows the search to a manageable handful of candidates. Easy-peasy.

For inputs I polled well-placed folks in the industry, and noted the few writers brave (or foolish) enough to weigh in on the selection process. I surveyed music groups on Facebook and Reddit, as well as some surprisingly active, old-school music chat forums. I scraped lists and listicles of emerging young conductors. I also sniped the names of all the Dudamel Fellows since 2009, as well as the winners and runners-up from conducting contests like the Gustav Mahler Conducting Competition, and Sir Georg Solti International Conductors’ Competition. This process yielded 129 names.

Then it was time to slop together data for each conductor. These included search results; mentions, follows and likes on social media; mentions across well-trafficked classical music sites; the entirety of each conductor’s recorded output, both audio and video; and each conductor’s relative popularity in the Los Angeles market. All that gets run through the DUDAMEL algorithm, which organizes, analyzes and weights the data before finally kicking out a list of names with a job-fitness ranking.

Bear in mind that the most important factors in a conductor search include the conductor’s rapport with the orchestra, their area(s) of expertise, their skill in handling personnel matters, as well as other considerations like audience enthusiasm. These are modelable in some sense, but not in this first version of D.U.D.A.M.E.L. We’re creating the short list. Let the committee do the rest!

THE LONGER LIST

So who made the list? Glad you asked.

FILTER 1: WHAT’S ON YOUR MIND?

Our project begins by asking prying questions about conductors on popular search engines. How old are they? Married or divorced? Ever been arrested? The people want to know! From there we progress to finer-grained details – on Wikipedia, or the artist’s agency bio page, or their personal website – and then on to Youtube, where you start to notice time unraveling. An hour ago (swear to god it was only five minutes) I knew nothing about this person. Now I’ve seen them conduct Xenakis at the Proms, endured an awkward interview on a Schenectady CBS affiliate, and discovered wobbly footage of them in a conducting masterclass at Sorbonne in 2011. Sensational.

Using these few sites as tools for an initial assessment of public interest, here are some names that land at the top of the pile:

| Name | Search hits | Youtube results | Number of Wikipedia footnotes (English only) |

| Gustavo Dudamel | 780000 | 1520 | 42 |

| Klaus Mäkelä | 153000 | 173 | 13 |

| Daniel Barenboim | 318000 | 1730 | 142 |

| Simon Rattle | 235000 | 843 | 68 |

| Zubin Mehta | 223000 | 1020 | 47 |

| Yannick Nézet-Séguin | 122000 | 589 | 43 |

| Antonio Pappano | 159000 | 548 | 21 |

| Valery Gergiev | 172000 | 749 | 46 |

| Myung-whun Chung | 165000 | 380 | 11 |

| Riccardo Muti | 181000 | 1160 | 44 |

| Andris Nelsons | 80200 | 432 | 38 |

| Esa-Pekka Salonen | 111000 | 518 | 67 |

| Marin Alsop | 113000 | 451 | 56 |

| Michael Tilson Thomas | 131000 | 349 | 28 |

| Lionel Bringuier | 60900 | 193 | 5 |

| Riccardo Chailly | 102000 | 439 | 27 |

| Franz Welser-Möst | 89700 | 394 | 19 |

| Daniel Harding | 66800 | 405 | 19 |

| Christian Thielemann | 78500 | 397 | 27 |

Now we’ve got results for our field across three categories. (If you’re interested, the search formulation was “firstname lastname conductor” and “site:youtube.com ‘firstname lastname conductor’” to minimize search clutter. Your mileage may vary.) But our job is to identify and evaluate lesser-known candidates, too. So this is just a start.

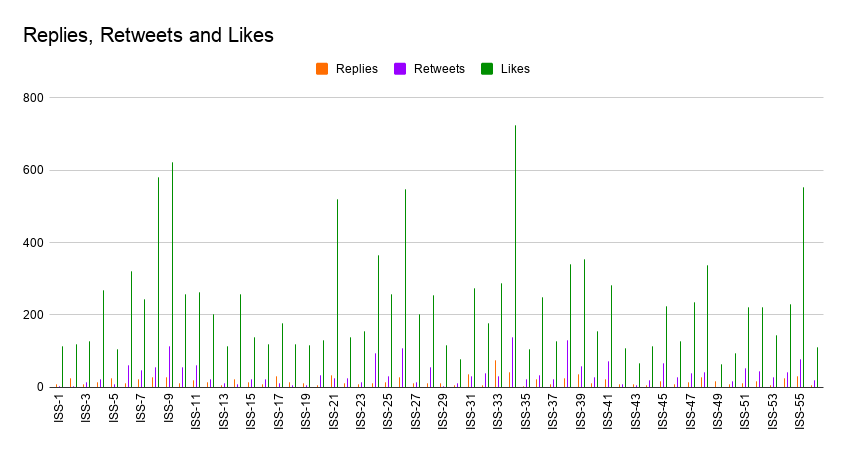

FILTER 2: THE SOCIAL MEDIA BUBBLE

Social media are an inescapable and sometimes regrettable part of online life. And while social media, smartphones, and a lack of IRL friends seem to have awakened in us some temporarily unsolvable malaise, they can and do tell us interesting things about public figures, if sometimes inadvertently.

Here’s an example to start:

| Name | IG followers | Twitter followers | Facebook followers | Sum | Age | Sum/Age |

| Gustavo Dudamel | 548000 | 815700 | 1100000 | 2463700 | 42 | 58659.52381 |

| Alondra de la Parra | 139000 | 302500 | 399000 | 840500 | 42 | 20011.90476 |

| Daniel Barenboim | 151000 | 54000 | 421000 | 626000 | 80 | 7825 |

| Teddy Abrams | 7291 | 4064 | 199000 | 210355 | 35 | 6010.142857 |

| Michael Tilson Thomas | 21500 | 123800 | 52507 | 197807 | 78 | 2535.987179 |

| Riccardo Muti | 16000 | 4437 | 123000 | 143437 | 82 | 1749.231707 |

| Yannick Nézet-Séguin | 65800 | 27300 | 43654 | 136754 | 48 | 2849.041667 |

| Lorenzo Viotti | 109000 | 0 | 4600 | 113600 | 32 | 3550 |

| Simon Rattle | 0 | 0 | 97095 | 97095 | 68 | 1427.867647 |

| Valery Gergiev | 75300 | 12200 | 0 | 87500 | 69 | 1268.115942 |

| Marin Alsop | 21000 | 15700 | 39897 | 76597 | 66 | 1160.560606 |

| Nathalie Stutzmann | 11500 | 3521 | 57708 | 72729 | 57 | 1275.947368 |

| Esa-Pekka Salonen | 9255 | 37100 | 20000 | 66355 | 64 | 1036.796875 |

| Teodor Currentzis | 3350 | 0 | 63000 | 66350 | 51 | 1300.980392 |

| Pablo Heras-Casado | 21800 | 9408 | 31000 | 62208 | 46 | 1352.347826 |

| Andris Nelsons | 19400 | 11700 | 28510 | 59610 | 44 | 1354.772727 |

| Christian Vásquez | 27300 | 10100 | 20000 | 57400 | 39 | 1471.794872 |

| Klaus Mäkelä | 40200 | 11200 | 5800 | 57200 | 27 | 2118.518519 |

| Diego Matheuz | 9322 | 5613 | 34000 | 48935 | 38 | 1287.763158 |

| Antonio Pappano | 21800 | 128 | 21074 | 43002 | 63 | 682.5714286 |

| Alan Gilbert | 3609 | 12500 | 16000 | 32109 | 56 | 573.375 |

| Karina Canellakis | 8295 | 6191 | 14000 | 28486 | 42 | 678.2380952 |

| Myung-whun Chung | 0 | 0 | 25000 | 25000 | 70 | 357.1428571 |

| Rafael Payare | 8858 | 6124 | 9400 | 24382 | 43 | 567.0232558 |

Here we’ve rolled up conductors’ followers from Instagram, Twitter and Facebook. Interestingly, if you then control for age (the far-right column) the list doesn’t change much. The old heads had a head-start career-wise, but social media are newer phenomena, and the playing field is more level.

My suspicion was that the action was mostly on Instagram these days but that is not the case – our candidates have over 3 million aggregate follows on Facebook, nearly as many as Insta (1.58 million) and Twitter (1.57 million) combined.

I don’t mean to infer anything by asking, but I wonder if anyone’s considered … buying followers? I guess I should first ask: are bot followers still a thing? If so, is it still gauche to pad the follower count with some friendly NPCs?

FILTER 3: DEEPER-LYING CLASSICAL FLAVOR

People get their first taste of classical info using search and Wikipedia and bending space-time in the Youtube spiral. But for hardcore consumers, a suite of sites offers granular news, niche recordings, exhaustive historical detail, and (mean-)spirited discussion of all these things. Our stops might include Bachtrack, ClassicsToday, Ludwig Van, NPR Classical, Sequenza21, Slippedisc, VAN, as well as groups on Reddit, Facebook (the best ones there are private), and so on.

Plugging our list into these sites yields a scattering of familiar names. Here are the 15 most prominent:

- Christian Thielemann

- Simon Rattle

- Gustavo Dudamel

- Kirill Petrenko

- Daniel Barenboim

- Fabio Luisi

- Valery Gergiev

- Yannick Nézet-Séguin

- Marin Alsop

- Semyon Bychkov

- Daniel Harding

- Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla

- Esa-Pekka Salonen

- Andris Nelsons

- Zubin Mehta

I should note that my inclusion of Dudamel is mostly for comparison’s sake. Dare the LA Phil hope for his return? Well, his NY Phil contract ends in 2031. It’s possible a 50-year-old Dudamel could boomerang back to LA like LeBron returning to the Cavs in 2014 – I’M COMING HOME and all that. But if things go sideways at Lincoln Center it’s easier imagining Dudamel in some sort of European sinecure – maestro’s lost weekend – before considering another one of these pressure-cooker positions.

FILTER 4: THE BACK CATALOG

There was a time when making records was the most important part of a musician’s job. The album was the artifact fans bought and pored over, dissected and debated. The recordings were synonymous with the artist: Glenn Gould and the Goldberg Variations; Fritz Reiner and the CSO doing Bartok’s Concerto for Orchestra; Stravinsky Conducts Le Sacre du Printemps; and on and on. These were the hymnals we read from.

Now the streaming era has blown all that up. Yes, there’s more music than ever at our fingertips. But it’s sat on anodyne playlists and best-of compilations, spread across platforms with nary a word of context.

The crowdsourced project-cum-marketplace Discogs has done its fair share of musical reclamation, and in addition to selling rare physical copies of albums they have extensively cataloged album releases past and present. So for instance, running our list of 129 names through their database nets these top performers:

| Name | Discogs credits |

| Daniel Barenboim | 1545 |

| Zubin Mehta | 1083 |

| Riccardo Muti | 852 |

| Simon Rattle | 620 |

| Riccardo Chailly | 581 |

| Michael Tilson Thomas | 550 |

| Valery Gergiev | 382 |

| Esa-Pekka Salonen | 363 |

| Iván Fischer | 285 |

| Myung-whun Chung | 248 |

Barenboim is linked with an astounding 19 recorded projects per year, an untouchable feat. How do younger conductors fare? Here are some whippersnappers (under 50 years old, we’re grading on a curve) in ascent:

| Name | Discogs credits / age |

| Daniel Harding | 2.833333333 |

| Yannick Nézet-Séguin | 2.208333333 |

| Gustavo Dudamel | 1.785714286 |

| Ilan Volkov | 1.739130435 |

| Andris Nelsons | 1.522727273 |

| Kirill Karabits | 0.9787234043 |

| Jakub Hrůša | 0.9523809524 |

| Maxim Emelyanychev | 0.5882352941 |

| James Gaffigan | 0.5681818182 |

| Pablo Heras-Casado | 0.5652173913 |

| Han-na Chang | 0.55 |

A classical music career can extend far beyond the range of “normal” ones, so in controlling for age we are simply dividing the number of projects by a conductor’s age. In other fields you’d say a career is roughly the time post-university to retirement. But conductors and musicians and composers are active outside those boundaries – and sometimes doing their best work, too.

FILTER 5: WENT TO CALI, GOT FAMOUS

Finally we find out who of these conductors is not just famous, but LA-famous. To do this we start with the archives at the town paper, the LA Times, and afterwards cross-reference with public radio site KUSC.org. KUSC is the official streaming partner for the LA Phil, so a mention there is nice.

Here are LA’s top ten richest and most famous:

- Zubin Mehta

- Iván Fischer

- Esa-Pekka Salonen

- Daniel Barenboim

- Michael Tilson Thomas

- Simon Rattle

- James Conlon

- Valery Gergiev

- JoAnn Falletta

- Riccardo Muti

But we should consider younger candidates with as much upside as experience. If we scuttle all previous LA Phil conductors as well as anybody over 52 we get an entirely different top ten:

- Lionel Bringuier

- Yannick Nézet-Séguin

- Andris Nelsons

- Matthew Aucoin

- Pablo Heras-Casado

- Daniel Harding

- Matthias Pintscher

- Lahav Shani

- Alondra de la Parra

- Jakub Hrůša

Right. That’s us done. To the algorithm!

ALGO TIME: TRUST THE MACHINE

The Data-driven Utility for Determining Artistic Merit and Evaluating Leadership has evaluated candidates and produced a first draft of our simulated search. Let’s have a look.

| Name | Fit |

| Gustavo Dudamel | 100.00% |

| Yannick Nézet-Séguin | 85.07% |

| Andris Nelsons | 85.07% |

| Daniel Harding | 85.07% |

| Alondra de la Parra | 52.24% |

| Pablo Heras-Casado | 52.24% |

| Klaus Mäkelä | 50.75% |

| Vladimir Jurowski | 47.76% |

| Lahav Shani | 46.27% |

| Paolo Bortolameolli | 37.31% |

| Lorenzo Viotti | 35.82% |

| Teodor Currentzis | 35.82% |

| Karina Canellakis | 35.82% |

| François-Xavier Roth | 32.84% |

| Lionel Bringuier | 31.34% |

| Jakub Hrůša | 31.34% |

| Kirill Petrenko | 29.85% |

| Teddy Abrams | 20.90% |

| Christian Vásquez | 20.90% |

| Diego Matheuz | 20.90% |

| Rafael Payare | 20.90% |

| Domingo Hindoyan | 20.90% |

| Dalia Stasevska | 20.90% |

| Kahchun Wong | 20.90% |

| Enluis Montes Olivar | 20.90% |

| Matthew Aucoin | 16.42% |

| Matthias Pintscher | 16.42% |

| James Gaffigan | 16.42% |

| Santtu-Matias Rouvali | 14.93% |

| Maxim Emelyanychev | 14.93% |

| David Afkham | 14.93% |

| Joana Mallwitz | 14.93% |

| Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla | 14.93% |

Unsurprisingly, DUDAMEL rates its namesake a 100% match for the position. The rest of the field are measured against him, such that Andris Nelsons is an 85.07% match, Karina Canellakis is 35.82%, Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla is 14.93%, and anyone else is out of consideration for this round.

But now it’s fair to admit that I’ve omitted a key piece of information: that the LA Phil – at least according to early speculation – is more likely to hire a woman for the position. We can easily adjust parameters to only include, say, the ten highest-rated women for the job:

| Name | Fit |

| Nathalie Stutzmann | 68.66% |

| Alondra de la Parra | 67.16% |

| Han-na Chang | 55.22% |

| Karina Canellakis | 52.24% |

| Susanna Mälkki | 47.76% |

| Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla | 46.27% |

| Elim Chan | 35.82% |

| Dalia Stasevska | 20.90% |

| Gemma New | 16.42% |

| Joana Mallwitz | 14.93% |

Now that’s more like it. For this, DUDAMEL automatically expanded the age range, which rockets Atlanta Symphony music director Nathalie Stutzmann to the top of our list, and rightly includes former LA Phil principal guest conductor Susanna Mälkki as well. We’re happy about both.

The algorithm also recalculated fitness ratings, which explains the difference between Alondra de la Parra in the first list (52.24%) and the second (67.16%). Our original list of 129 conductors predominantly features men, which is an unfortunate reflection of job searches like these. When it selects for women obviously all get a ranking boost.

So we have ten candidates, which is hardly a daunting number, and in fact at this point the search committee might simply book each for a week of hands-on orchestral work. The remaining considerations include polling the players, gauging audience reaction, and selecting someone. Done.

POSTSCRIPT

What we’ve done is a poor man’s version of a McKinsey consult, using rudimentary survey methods, an excessive amount of searching and scraping, and AI assistance to move the process along. This modeling reveals a rather large deficit in publicly-available, quantifiable knowledge about conductors specifically, and classical music more generally.

It’s not ideal that our results so closely mirror conventionally-accepted picks. As Tyler Cowen notes, “We tend to visualize future events very poorly and with a deficit of proper imagination.” So in that spirit we should want to surface more wildcard picks, the less-obvious candidates – even at the risk of being wrong. Sounds like a job for DUDAMEL 2.0.

***

Subscribe to the CDA mailer – our occasional, 100% spam-free newsletter – and never miss a drop.