I’ve admired Steven Isserlis’ playing for decades. The first time I read his name was in a late 1990s profile of his teacher, Jane Cowan, in The Strad. When I got to university I spent so many hours in the listening lab and practice room pilfering ideas from Isserlis’ recordings of Boccherini cello concertos and Beethoven sonatas I should’ve paid royalties for jacking his IP. I obsessed over his Mendelssohn d minor sonata with Melvyn Tan on pianoforte — listening with headphones in between classes and on the long walk to and from school, then later at home where the low notes rattled through my speakers. That was back in the early aughts.

Now I spend less time studying classical cello and more time on a computer, which is, to put it mildly, a downgrade. Still, when scrolling Twitter a while back I was happy to come across a few tweets from @StevenIsserlis. My cello hero! Here on this sordid platform, with me and all the other poor souls! I followed him.

Isserlis appeared to do his own posting, rather than farming it out to an assistant or PR flak. He tweeted here and there, mostly on-brand stuff about composers or upcoming shows. He seemed to share a lot about dreams and nightmares he’d had. His kvetching about the minor agonies of travel was some of the best material.

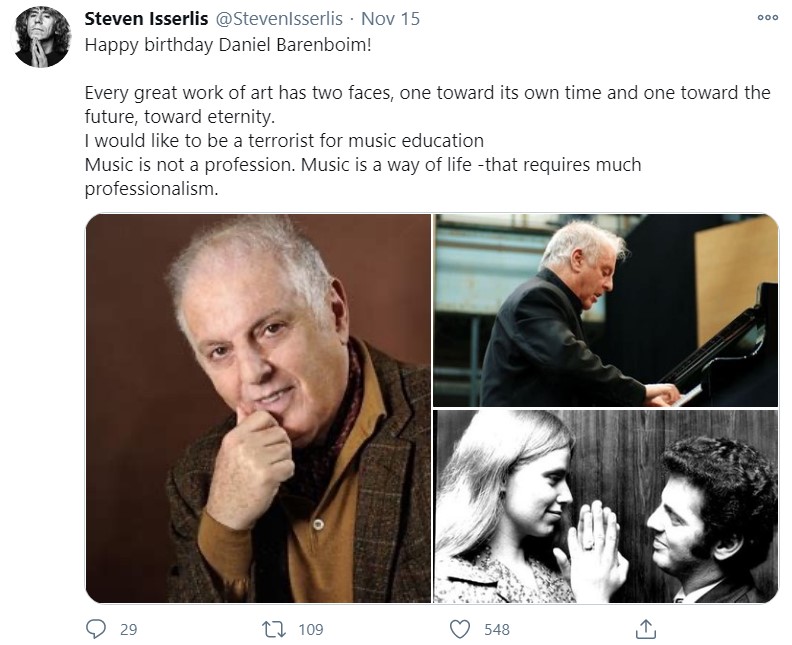

I didn’t give Isserlis another thought until his first tweet of the day on November 15th. The post in question was a fawning birthday message for Daniel Barenboim which, fair play, was probably as much a professional courtesy as anything else. Still, I recoiled. Barenboim was outed last year in VAN Magazine for allegedly abusive behavior, the type of thing slimy conductors got away with a generation or two ago, but now even allegations of which might get you shit-canned. Why was Isserlis singing a paean, like this, in a public forum?

I hedged on what to do. I dropped the VAN link in the comments. I debating unfollowing. But to what end? It’s possible I was just looking to get lathered up about something that more or less had nothing to do with me. (Hey, it’s Twitter, that’s the whole game.) But maybe the time had come to assess whether Steven Isserlis was, in fact, A Good Guy.

Sometimes it’s best to arm yourself with a truckload of data when faced with a tough decision. In this case, I needed to take a long-range account of things, and afterward to come to some conclusion. So I decided on a month-long study of Steven Isserlis’ Twitter timeline: I’d round up all his tweets, line them up front-to-back, and see what was there, down to the minutest detail. Collect it all, no judgements, and see what emerged. It was time to get back to the lab.

Background: How it Started, How it’s Going

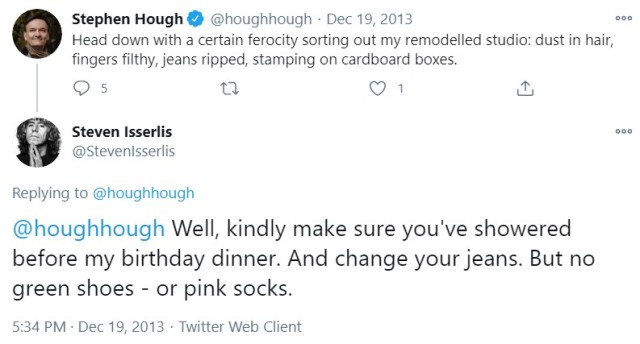

Isserlis began his Twitter account in July 2013 but didn’t actively tweet until later in the year, sometime in December as far as I can tell. Here’s a winking sartorial directive that appears to have been his first tweet.

To this day Isserlis hasn’t been verified — no blue check mark — but he boasts a respectable 21,184 followers while following 690 accounts (as of 16 December 2020). As I mentioned, Isserlis appears to do his own tweeting, and not at any great rate. You might expect him to post once or twice a day, with a few extra replies here and there.

The Limitations of The Study

I was interested primarily in what drives Steven Isserlis to his computer to tweet. To that end, I collated Isserlis’ initial posts while mostly ignoring follow-ups or replies he sent to others. Often Isserlis wades into comments to clarify something in his original post, or to respond to a question or a joke from a follower. While interesting, I suspected these replies weren’t his reason for tweeting in the first place. Also, Isserlis appears to be a prolific user of the Like button. Collating and analyzing these would be a fun future project, but it is beyond the scope of this study.

I alone was responsible for the parsing, screenshotting, cataloging and analysis that follow. All mistakes are my own. I am not a statistician or any type of data analyst; I’m a musician and author of the occasional newsletter. If you spot obvious errors, or if you’d like a copy of the spreadsheet I used, email me (first dot last at gmail) and I will gladly help.

Overview: The Public Collection

I took screenshots of 56 tweets sent out by @StevenIsserlis in the period between 12:00 AM on 1 November 2020 and 11:59 PM on 30 November 2020. I then noted the following details about each tweet.

- the time, day, and date sent;

- any accounts and/or people tagged in tweets, as well as the professions or affiliations of the tagged entities; and any entities or people mentioned without being formally tagged, as well as their professions or affiliations;

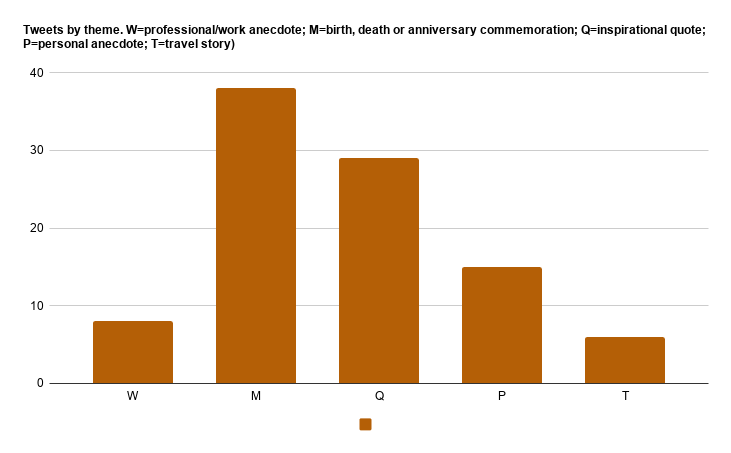

- the “category” of the tweet (arbitrarily determined; I settled on “personal anecdote,” “professional or work anecdote,” “birth, death or anniversary commemoration,” “inspirational quote,” and/or “travel story,” with many tweets residing in multiple categories);

- any picture(s) included in each tweet; and,

- how many replies, retweets and likes each tweet received.

The Data, Part One: When the Birds Flew Out

We are in the middle of a pandemic. It’s sometimes surprising to realize that even very famous or accomplished or well-traveled people are grounded in pretty much the same ways we all are. So what we’re seeing from Isserlis may actually be quite different online behavior than what he was up to pre-pandemic.

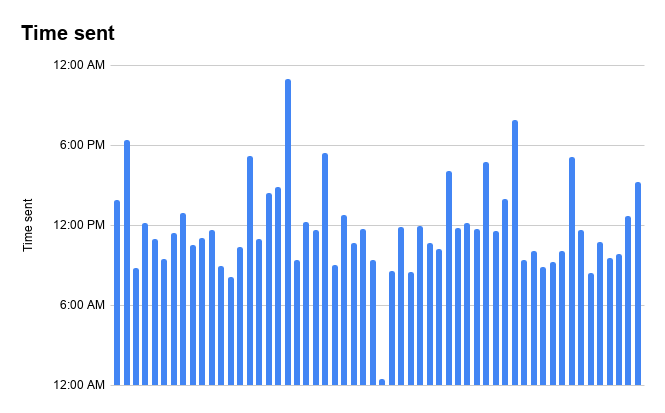

Mid-pandemic Isserlis seems driven to post in the morning. Not early early, mind, but generally if you’re fiending for new Isserlis content you’ll see something come across between 9 a.m. and noon. His average tweet time is roughly 11:50 a.m. across 30 days (with a median time of 11:30 a.m.), but that includes some statistical noise like a tweet about Jane the Virgin that came in 12:29 a.m. Not the usual office hours! If you remove that, as well as a few odd-hours travel tweets (more on these below), you get a pretty good idea when Isserlis decides to flip open his Alienware laptop and fire one off.

Isserlis is slightly more likely to tweet on Tuesdays and Wednesdays. His total count was: 9 tweets sent on Sundays, 9 on Mondays, 9 on Tuesdays, 9 on Wednesdays, 7 on Thursdays, 5 on Fridays, and 7 on Saturdays. Since November had an extra Sunday and Monday this year, removing those two dates allows us to state that the best time to expect a Steven Isserlis tweet is on a Tuesday or Wednesday, sometime between 11 a.m. and noon GMT.

The Data, Part Two: Cast and Crew

Because Isserlis does his own tweeting we’re spared the hectic and far! too! enthusiastic!!! posts of an empowered assistant or some hired-gun social wizard. We also avoid posts cluttered with a thousand twitter handles from hundreds of gigs, appearances, and shout-outs. This was something I didn’t fully appreciate until I started parsing all his tweets: a real human behind the controls.

Here’s the list of everybody Isserlis manually tagged in November:

- @wigmore_hall, the London concert hall

- @SimonCallow, actor, writer and director

- @houghhough, pianist Stephen Hough

- @BBCRadio3, tagged three times

- @DonaldMacLeod01, BBC Radio 3 host

That’s it! How refreshing. Obviously that’s not a lot to go on, so it was necessary to tally up all the names without ties to official handles, or of those deceased, or those who went untagged, and assemble them in groups by profession. This is where it gets interesting.

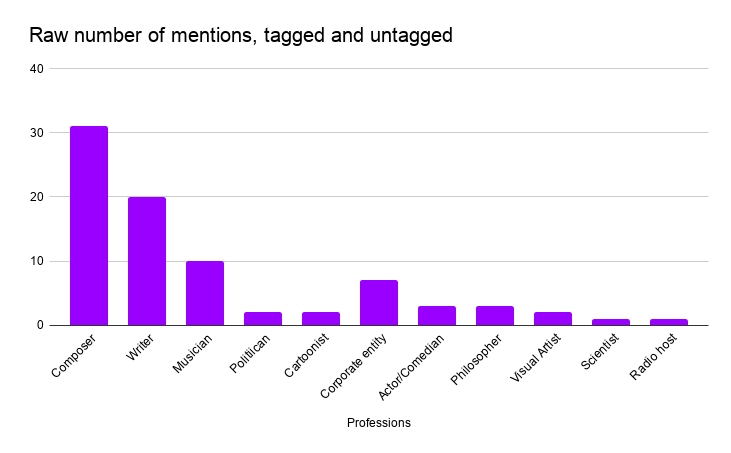

Unsurprisingly, Isserlis’ timeline features lots of composers and musicians. (I differentiated between the two by calling someone like Beethoven a composer, even though he was clearly a skilled pianist. Somebody like Miles Davis I called a trumpet player even though he was obviously a composer, too. I let a fearsome pianist like Rachmaninoff exist in both categories, since he’s known for composition and piano performance about equally. Not a perfect system, I acknowledge.) Isserlis brings up authors and philosophers quite often, suggesting both that he is a bit of a bookworm, and a lover of a good turn of phrase — unsurprising given his penchant for sprinkling quotes on tweets.

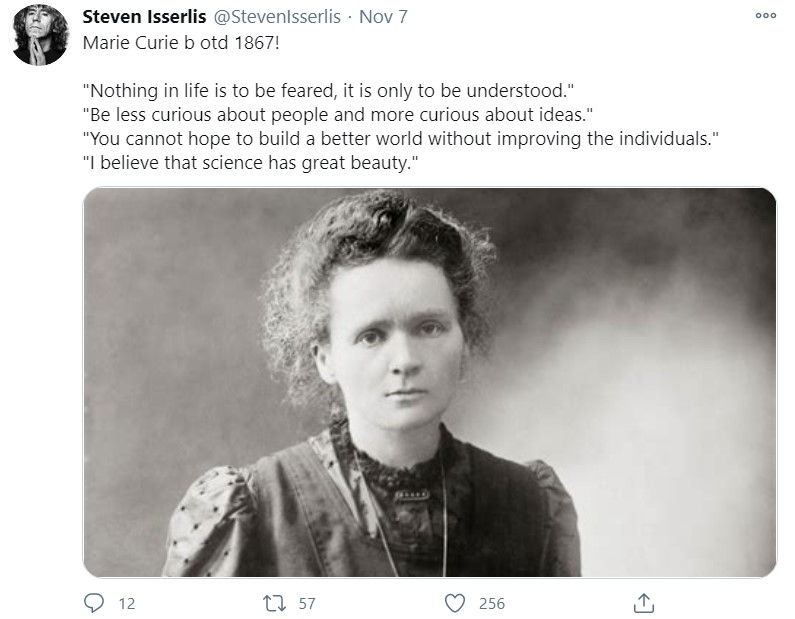

The corporate and business entities referred to here included Heathrow Airport, Uber, Netflix, Wigmore Hall, and BBC Radio 3. Not a lot of brand love there, which is, again, refreshing. Winston Churchill and Bobby Kennedy were the two politicians, and Marie Curie the lone scientist.

This tweet brings us to a crossroads. If we set aside business and other non-human (or arguably, inhuman) entities, Isserlis mentions 73 people over the course of the month, with some names — like J.S. Bach — appearing multiple times. However, in all only two women are ever featured or even mentioned: Madame Curie, and writer George Eliot, a.k.a. Mary Ann Evans. That seems rather low, no? Minorities and people of color seem to fare just as badly, although I didn’t research the ethnic and racial backgrounds of each person mentioned to arrive at precisely what number.

I have no doubt Isserlis is a forthright and enlightened citizen, and I’m sure he’s used his powers, offline, to amplify lesser-heard voices in some capacity. However, when you’ve got 21,000-plus followers on Twitter, and when you wield the type of power that Isserlis does in the music world generally, I would say this disparity we’ve discovered is worth flagging.

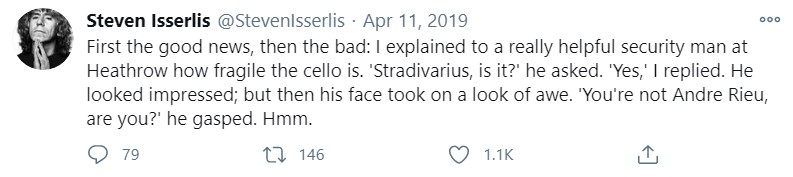

The Data, Part Three: Herding Cats

I noted that in the past Isserlis tweeted a lot about the vagaries of travel. It makes sense. Traveling by air is generally terrible. Traveling with a cello — let alone an expensive Stradivarius, Montagnana, or Guadagnini — is far worse. So Isserlis took to Twitter to vent and produced, I would argue, some of his best content.

Obviously the story is different these days. In order to assess what preoccupied mid-pandemic Isserlis — at least what he was willing to publicly share — it was necessary to develop a rubric for analyzing these posts. As stated above, the categories are: “personal anecdote,” “professional or work anecdote,” “birth, death or anniversary commemoration,” “inspirational quote,” and/or “travel story.” A majority of the tweets fell into multiple categories. Here’s how I broke them down.

Consider the following tweet.

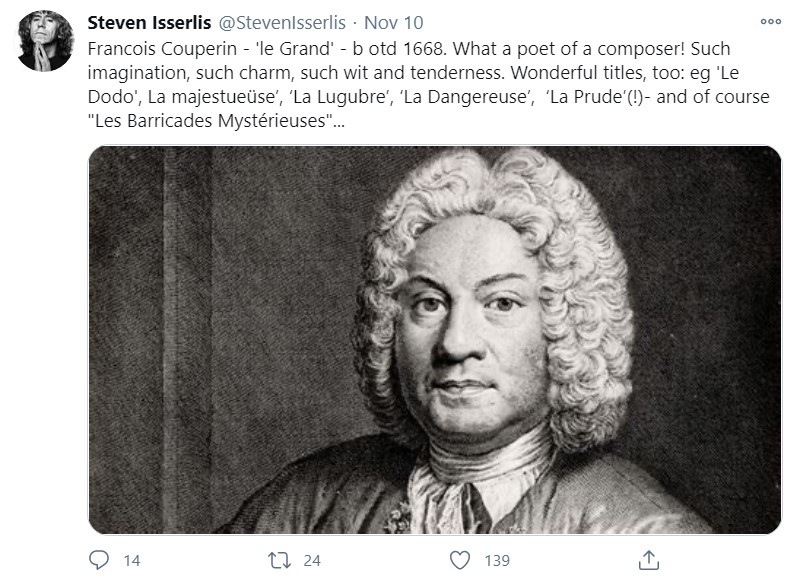

This is categorized as M for “birth, death, or anniversary commemoration.” These are some of Isserlis’ most common tweets, a template he returns to again and again. (The Barenboim tweet would qualify.) He can’t resist a good birthday, a lamentable death date, or the anniversary of some great work. Then there’s this:

Now we’ve got some pleasing stock photos (of paintings) to work with. We also enter a separate content category: quotes. Many memorial or commemorative posts feature quotations, so I labeled this Monet post as “M/Q” to reflect its dual role.

This one is trickier.

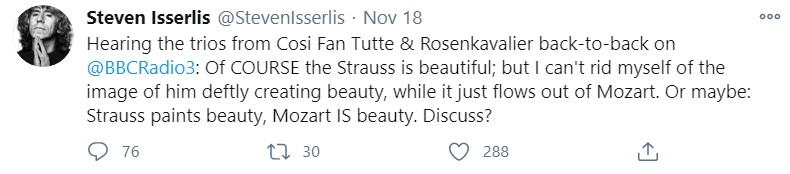

I gave this one a P for personal anecdote because we can assume Isserlis was relaxing at home, or maybe whipping around in his McLaren P1, vibing and listening to BBC Radio 3. But since he’s sharing a somewhat analytic thought about classical music (work-mode: activated) I went with W/P.

We did get travel tweets in November, after all. His posts suggest Isserlis flew to Madrid on Tuesday, 10 November and returned sometime after Friday, 13 November. We know this because he sent out a travel tweet the morning of the 10th name-checking the dreaded Heathrow Airport. Thereafter followed several tweets about masked rehearsals, conductors’ doors backstage, and even one with photos of city sites. Further, tweets that normally went up using the Twitter Web App were suddenly (although not exclusively) posted using Twitter for iPhone. More authoritatively, Isserlis’ own web page confirms he did a two-night stint at the Teatro Monumental, playing the Haydn D Major concerto with Orquesta Sinfónica de RTVE and conductor Anu Tali.

Some tweets simply couldn’t be confined to one or two categories, such as this one.

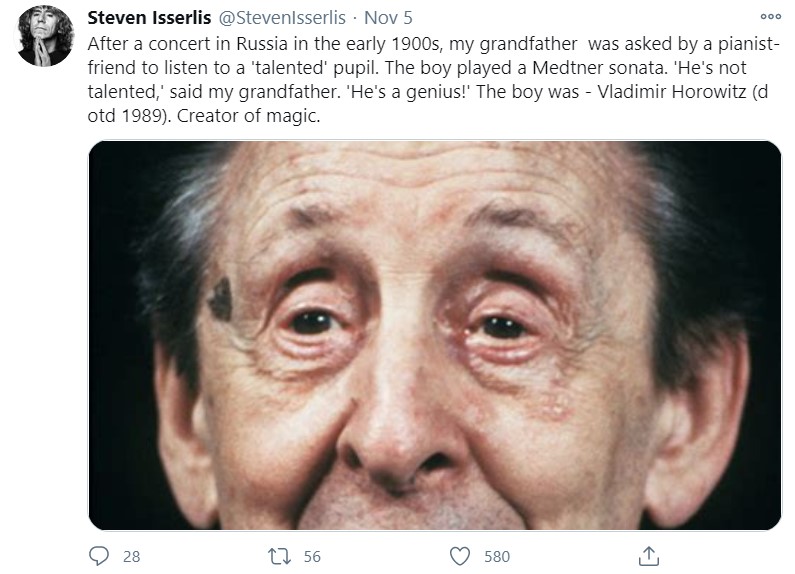

We’ve got the makings of a Vladimir Horowitz memorial post, complete with attached stock photo. But then we tap into Isserlis family history with Steven’s pianist grandfather, Julius, in a supporting role. And you better believe there would be a quote! So: a tidy M/Q/P combo. This is arguably work-adjacent so it could theoretically carry that label too, but you could say the same for nearly all of these. So I left it alone.

The Data, Part Four: Exposure Counter

Isserlis’ Twitter feed featured 60 images over the course of the month. Usually he posted an image available through Creative Commons, which is suiting for the types of OTD (“on this day…”) posts he’s partial to. Most of the people are long dead, their images old enough to be swiped from Wikipedia. Some are actual photographs, while others are photos of paintings (or of engravings and other such things).

For subjects for whom he appears to care a great deal he’ll add a second or even third photo. The now-infamous Daniel Barenboim post came with three-pack of glamour shots. Robert Louis Stevenson also got a three-photo salute. Isserlis maxes out his full four-photo allotment if the subject merits it, such as here with Harpo Marx (about whom Isserlis feels very passionate indeed).

Others who got the four-photo treatment include pianist Radu Lupu — Isserlis himself appearing in one photo, the only such example in November — and actor and comedian Peter Cook.

Isserlis isn’t shy about opening up the iPhone camera roll when the occasion demands, like for this backstage pas de deux from Madrid.

And later emerged a trio of night shots.

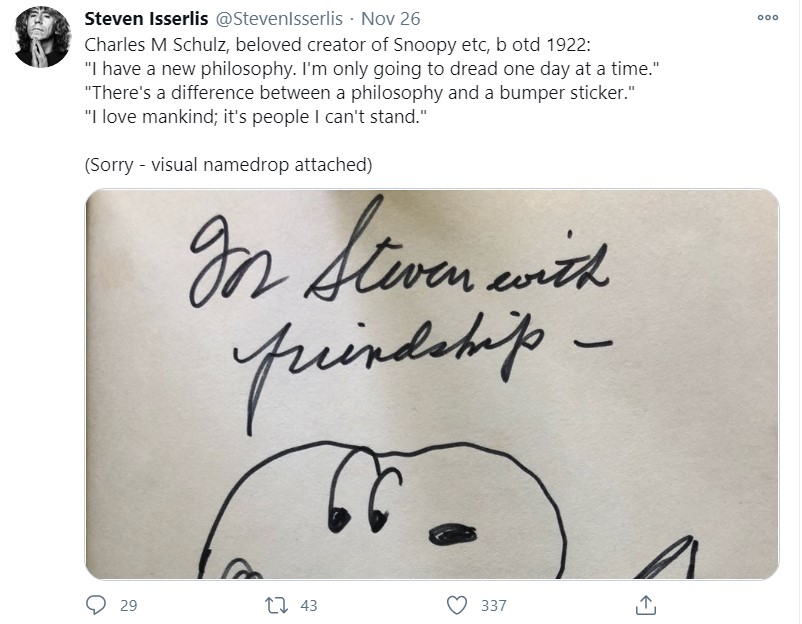

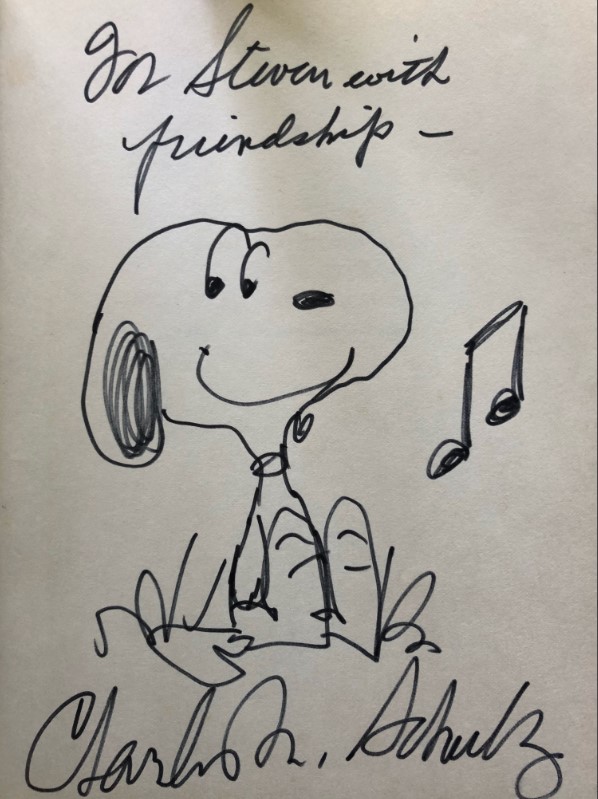

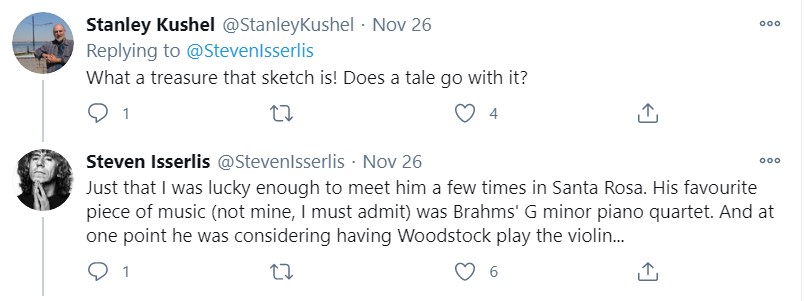

The best photograph he posted, at least to my mind, was one likely retrieved from somewhere in the back of a dusty file cabinet. The post starts as — yes, you guessed it — another OTD tweet, but goes up a level.

Peanuts creator Charles Schulz was known to send doodles in response to fan letters. How did Isserlis come by this gem? Was he, is he, a ride-or-die Peanuts fan? Can he correctly rank the animated Peanuts holiday specials? (For the record it goes: 1. Christmas, 2. Halloween, 3. New Year, 4. Easter, and distantly, 5. Thanksgiving.) I had questions.

I decided to break one of my own rules for the project: I scrolled through the replies, and found the answer right away.

Contra Isserlis, I agree with Schulz that the Brahms’s first piano quartet is a fine piece of music. And Woodstock on the violin! Imagine what he and Schroeder could’ve gotten up to.

The Data, Part Five: How Deep is Your Love

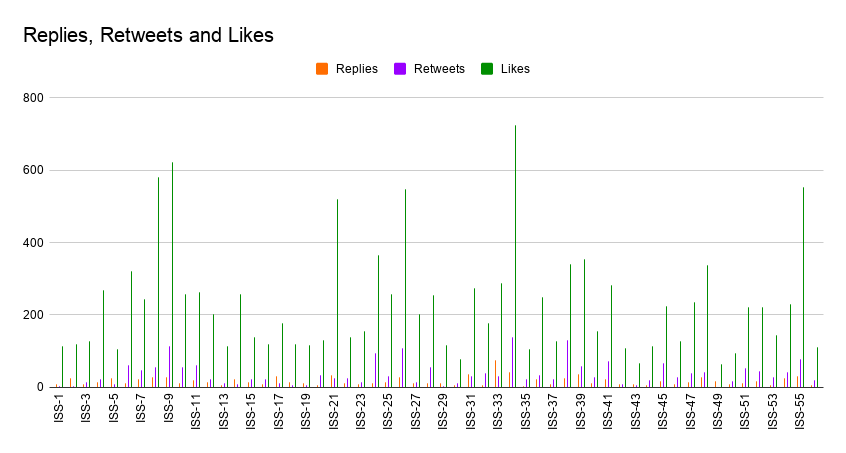

Now we get to the rudimentary measurements of reach and popularity embedded into the public-facing side of the Twitter app: replies, retweets, and likes. These metrics are starting points for determining roughly how popular certain posts are. Their relationship to one another (see: The Ratio) sometimes indicates more than a simple raw number of likes or retweets does. Generally they are imperfect measurements, since the person tweeting lacks absolute control over the reception to their own tweet (obviously).

On an average post in November, Steven Isserlis generated 17.91 replies, 37.68 retweets, and 231.96 likes. (Median numbers: 14 replies, 28 retweets, 202.5 likes.) The following received the month’s highest number of replies: 76.

Meanwhile, this post about Schubert (OTD, baby!) hit the month’s high-water mark for retweets (138) and likes (726).

While we can speculate whether it was the god Schubert himself who supercharged this tweet’s performance, it’s just as likely a timely retweet carried it. (Or the fact that Isserlis did a swan-dive into the replies and stayed active for a good period. Again, I don’t have comprehensive information on his behavior elsewhere to compare it to.)

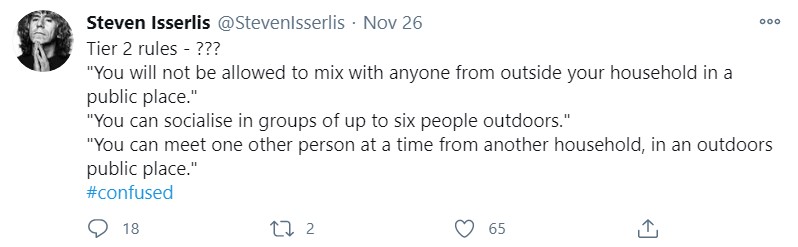

Cruelly, the least number of retweets for a post came on 26 November, when Isserlis broke with mostly arts-and humanities-related content to muse on pandemic regulations.

Can’t blame him for being confused. That’s everybody right now.

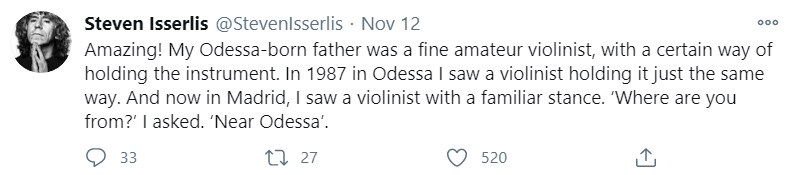

A subset of tweets (six in total) exceeded 400 likes. What were they? The Schubert post, the Horowitz post, as well as ones about Tchaikowsky, Isserlis’ father, Radu Lupu, and Barenboim. What do they have in common? Five of six were memorial or commemorative in some way. The sixth was a charming story from the middle of the Madrid trip.

As I mentioned, social media engagement is a tricky thing to properly measure, and in fact carries very little import vis-à-vis our final goal. But it does allow a bit of insight. As a reminder, the average Isserlis tweet garnered 17.91 replies, 37.68 retweets, and 231.96 likes. But if you select only his OTD memorial posts you have an average of 16.71 replies, 45.87 retweets, and 251.11 likes. So, although it’s hard to intuit, the engagement levels may (or may not) subconsciously nudge Isserlis into producing more rather than fewer of these posts. But maybe a simpler explanation is, he just enjoys doing them.

Results: That’s it. That’s the Tweet

I say with a high degree of confidence that we have spent more time in the slipstream of Steven Isserlis’ tweets than he’s likely spent thinking about Twitter, ever. But the point was to temporarily ignore the matter in question (the Barenboim thing) to focus forensically on everything else. And in doing so, hopefully, arrive at an acceptable answer.

One of the problems with classical music is that the repertoire leans heavily on dead white guys, to the exclusion of pretty much everyone else. This has been well documented and debated. No need to rehash here, except within this context: that throughout November, Isserlis’ account read like a rolling appreciation thread for all the usual suspects, no different from the types of stale programming and thinking that brought us to this point.

People like Rob Deemer have created invaluable resources like the Institute for Composer Diversity to start to rectify just such problems. But the hard part isn’t marshalling resources like this — it’s convincing orchestral organizations, patrons, presenters, conductors, artistic directors, players (ahem), and audiences that women, people of color, and those with backgrounds atypical for classical music are worth championing, promoting, and supporting most energetically.

I don’t want to come off like a scold or a small-time internet sheriff. If anything I want Isserlis to push the envelope further, to be edgier. He has it in him. But if my original question was, Why post the Barenboim thing at all? Then the answer is: stubbornness, or more cynically, intellectual flabbiness. For an artist of Isserlis’ caliber that’s unacceptable. He’s got the power to wire up his fanbase with new ideas and new projects. And yet, here we are.

I popped back on Isserlis’ timeline again recently and was glad at least to see that he’s upped the number of women who’ve appeared on his timeline — so far six (!) and counting for December. But then I saw a post about Woody Allen. I closed the tab.

One reply on “A month-long forensic examination of a star musician’s social media feed (Steven Isserlis please don’t block me)”

Nice blog thannks for posting